Discover the Rich History of the Salt River Community

The territory of O’odham and Piipaash along the Salt River was originally recognized by the U.S. government via executive order, signed by President Rutherford B. Hayes on January 10, 1879. Unfortunately, a subsequent executive order on June 14, 1879 reduced the Salt River reserve from approximately 680,000 acres to just 46,627 acres. The second order also created two disconnected land bases, separating the Salt River O’odham and Piipaash from their relatives living along the Gila River.In 1940, the Salt River Community adopted a constitution and bylaws under the provisions of the federal Indian Reorganization Act and is now governed by an elected president, vice president and Tribal Council.

Early History

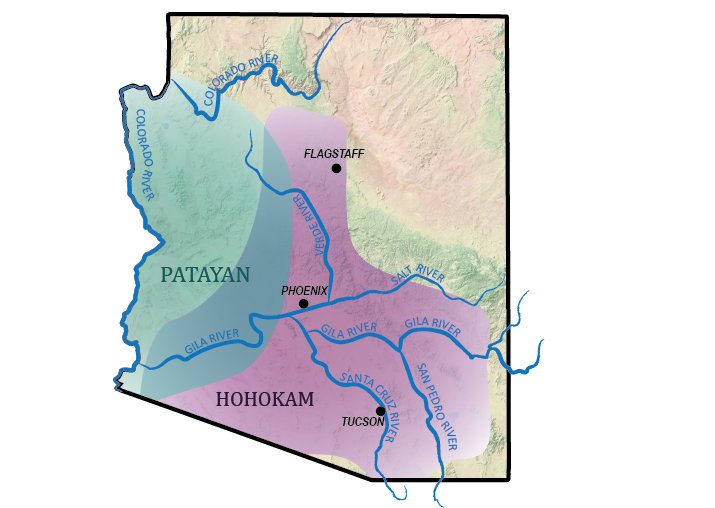

The interaction between our two tribes began long before the first Europeans arrived in our territory. Along the lower Gila River, there are ancient sites that indicate frequent interaction and co-habitation among those whom archeologists refer to as Hohokam and Patayan.

“Patayan” is a term used by archaeologists to describe a prehistoric archaeological culture that inhabited parts of modern-day western Arizona, southeastern California, northern Baja California, and Sonora, Mexico. They are ancestral to the contemporary Yuman tribes, including the Xalychidom Piipaash.

“Hohokam” is a term used by archaeologists to define a prehistoric archaeological culture that inhabited a large part of central and southern Arizona. The core Hohokam culture, however, was located in what is today the Phoenix Valley. They are ancestral to the contemporary O’odham tribes, including the Onk Akimel O’odham.

The use of archaeological terms for prehistoric time periods sometimes creates confusion for the layperson, leading many to erroneously believe these terms were the actual names of tribes who resided here for a limited time, then somehow vanished (see: Huhugam vs. Hohokam). When Eusebio Kino, one of the first Spaniards to visit our homeland, traversed the Gila River in the 1690s, he of course found the O’odham and Piipaash residing and interacting in the same areas as our ancient ancestors.

By the time the first Spanish explorers arrived in our territory, we had abandoned some of the more elaborate aspects of the material culture our ancestors had previously maintained. We had vacated the large adobe structures, such as those found at Pueblo Grande, Casa Grande, and Mesa Grande. The reasons for this are complex and not completely agreed upon.

There are a number of scientific theories as to why the culture and population density changed dramatically around 1450. Our own oral histories regarding this time frame are equally complex. Perhaps the fundamental reason is that a modest lifestyle is simply more sustainable in this harsh Sonoran Desert environment.

Our ancestors developed the most advanced canal system in North America. Hundreds of miles of canals were engineered and dug by hand to provide irrigation water to villages that were located great distances from the river channels. Historic O’odham and Piipaash maintained this tradition of canal farming, and our ability to produce an abundance of food was an important contributing factor in shaping relations with other tribes and non-natives early on. Some of these prehistoric canal courses are still utilized in the Phoenix Valley today.

Post Contact

Early Spanish, Mexican, and American contact was generally cordial. Therefore, written history has largely recorded us as being docile farmers who never warred with anyone. In reality, the O’odham and Piipaash confederation had one of the most formidable military forces in the area. Such a force was necessary to protect our fertile and bountiful riparian farmland.

Despite the ability to muster a strong military force, the cultures of the O’odham and Piipaash were friendly, welcoming, and generous by nature, as corroborated by many early American civilians who passed through our territory. Early Americans relied on our military confederation for protection as they travelled through the area. Two hundred O’odham and Piipaash warriors were among the first to enlist for federal service with the inaugural Arizona Volunteer Infantry.

By the 1870s, however, the population of Americans in our territory dramatically increased, as did the competition for natural resources. When the rivers were diverted and dammed, our traditional lifeways changed dramatically. Without the life-sustaining rivers, the fields dried up, the forests of cottonwood and willow died off, and the grasslands disappeared.

Today, we, the Onk Akimel O’odham and Xalychidom Piipaash of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, strive to maintain the most important aspects of our traditional cultures as we simultaneously endeavor to survive and thrive among the culture of the majority population that surrounds us. The delicate and sometimes challenging balance of living in both worlds is imperative to the success of future generations.

Timeline of O’odham Piipaash History

Creation/1400 B.C.-8000 B.C. Paleo-Indians: Archaeologists have termed the cultures of this time period as Paleo-Indian. They are scientifically identified as small mobile groups who hunted mega fauna. O’odham and Piipaash Creation stories don’t delineate specific dates, but they do recount events that establish local spaces as our places of origin and continued inhabitation. The O’odham refer to all departed ancestors as Huhugam. The Piipaash refer to those who came before us as Piipaa nykor.

8000 B.C.-A.D 1 Archaic Period: Archaeologists also termed this time period as such, defining it as a time where the local indigenous populations began to settle into small villages and practice agriculture. In our own languages, we refer to our ancestors from any time period as Huhugam and Piipaa nykor.

A.D. 1-1450 Hohokam: O’odham ancestors occupy vast areas of land in modern-day central Arizona, but especially large settlements are established along the Gila and Salt Rivers. We would call those river settlers Akimel O’odham (River People), distinguished from the desert settlers, the Tohono O’odham (Desert People). Archaeologists borrowed the O’odham word Huhugam and used the modified term, Hohokam, in a more restricted way to classify an archaeological culture with a limited temporal frame. The original O’odham word is not limited to the same time frame; rather, it extends from the beginning of time to present.

A.D. 500-1550 Patayan: The term, Patayan, is used by archaeologist to describe a prehistoric culture that is distinct from the Hohokam culture and occupied an adjacent territory in what is modern-day western Arizona, southeastern California, Baja California and Sonora, Mexico. The Patayan people are ancestral to contemporary Yuman-speaking tribes, including the Piipaash. Along the lower Gila River there are sites that indicate significant interaction and probable cohabitation among some Hohokam and Patayan peoples. Historically, this is the same general area where O’odham and Piipaash interaction and cohabitation existed prior to and at the time of European arrival.

1694-1854 Hispanic Period: The Akimel O’odham and Piipaash, although different in language and custom, form a more formal alliance. O’odham and Piipaash villages are concentrated along the Gila River due to increasing conflicts with the Quechan, Mojave, Yavapai and Apache. We continue to utilize areas along the Salt River for fishing, hunting, gathering and farming, but consider the area too dangerous to maintain villages at this time. Spanish missionaries and subsequent Mexican settlers arrive in small numbers. Relations with them remain generally friendly, as they seemingly pose little threat. O’odham relatives to the south, however, mount intermittent revolts against the Spanish as they began to experience a gradual loss of autonomy and territory.

1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: The Mexican-American War ends. The U.S. annexes territory formerly claimed by Mexico. The annexed area includes the Salt River. The Gila River designates the new border between the U.S. and Mexico.

1849 Gold Rush: This year and years following, the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash protect and provide supplies for thousands of weary American travelers en route to California. These newcomers seemingly pose little threat and trade increases our prosperity.

1853 Gadsden Purchase: The U.S. purchases additional lands claimed by Mexico to establish the U.S. and Mexico border as we know it today. The purchased area includes the Gila River and lands occupied by Akimel O’odham and Piipaash villages. The Akimel O’odham and Piipaash continue to assist civilian travelers, and now provide food supplies for the U.S. military as well. Relations with Americans remain cordial and there is seemingly little threat to our autonomy and territory.

Feb. 28, 1859 Gila River Reserve: The original Gila River Reserve is established by an act of congress, and $10,000 in gifts are allocated to the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash for loyalty to the U.S. government. This reserve, however, does not include traditional farming, hunting and gathering territories, nor does it include all existing Akimel O’odham and Piipaash villages. At this point in time, some Akimel O’odham and Piipaash begin to grow suspicious of American intentions as a result of unkept promises and a government survey conducted in our territory that suggests possible future encroachment. American civilians and the U.S. government continue to rely on the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash for food supplies. Akimel O’odham and Piipaash farmers reportedly sell more than 1,000,000 pounds of excess wheat to the U.S. military in 1862.

1865-1866 Fort McDowell: Piipaash & Akimel O’odham warriors serve as the first Arizona Volunteer Infantry at Ft. McDowell to assist the U.S. in the “Apache Wars”. Company B is comprised of 103 Piipaash volunteers. Piipaash traditional leader and medicine man, Juan Chivaria, assumes the highest rank of all Native volunteers (Captain). Company C is comprised of 94 O’odham volunteers. Traditional leader, Antonio Azul serves as the highest-ranking O’odham (Second Lieutenant). Our participation in this campaign served two purposes: to secure our own villages from increasing Apache raids and maintain positive relations with Americans.

1867-1870 Water Diversion: With the defeat of the Yavapai and Apache, more non-native civilians and entrepreneurs begin to settle into our territory, diverting Gila and Salt River waters for their own use. In 1867, Jack Swilling establishes the Swilling Irrigation Canal Company where the modern-day Phoenix Valley exists. Settlers around the Florence-Adamsville area begin diverting the Gila River for their own use. No longer needing the protection of the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash, many newly arriving non-natives have no regard for indigenous water and land rights. With the disruption of the river’s natural flow, the once prosperous Akimel O’odham and Piipaash find it increasingly difficult to raise crops. Thus begins an era that has come to be known by some as the “forty years of famine”. By 1869, some frustrated Akimel O’odham and Piipaash appropriate food from non-native fields. For the first time, the potential for serious conflicts arise between Americans and the Akimel O’odham-Piipaash confederation.

1871-1872 Reclaiming the Salt River: Akimel O’odham and Piipaash villages along west end are completely dry at times due to water diversion by non-native settlers. Annual reports to the Commission of Indian Affairs record that many O’Odham and Piipaash are leaving the Gila to resettle along the Salt River. Some O’odham and Piipaash are now suggesting war against the American settlers. Although Akimel O’odham and Piipaash tribal leaders realize their military force is powerful enough to forcibly remove the new settlers, they make every attempt to seek a peaceful resolution. For some, the choice of resettling ancient farmlands along the Salt River prevails over the choice of exercising military strength.

1873-1874 Proposed Relocation: The Board of Indian Commissioners recommends to President Grant that the O’odham and Piipaash along the Gila River should be relocated to Oklahoma Indian Territory. Tribal leaders visit the proposed territory to see if the land is truly as prosperous and fertile as described to them. The following year brings an abundance of rain and good crops, so the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash have no desire to relocate. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Edward Smith, also proposes relocating the Akimel O’odham and Piipaash to the Colorado River Indian Reservation. There is no forced relocation.

1876 Addition to Gila Reserve: 9,000 acres of land is added to the Gila River Reserve around the Blackwater District. This does nothing to solve the water rights issue, nor does it provide any real assistance. It merely reserves lands that are already occupied by Akimel O’odham. New Commissioner, Ezra Hayt, rekindles the idea of relocation to Oklahoma.

1877 Mormon Companies: Daniel Jones leads a small party of Mormon settlers from Utah and sets up camp along the south side of the Salt River in what is today north Mesa. The area in which Camp Utah was built would eventually be called Lehi. Although relations with Americans have been strained, they have not completely disintegrated. Positive relations remain established with those who treat us fairly and respectfully. A group consisting primarily of Xalychidom Piipaash and some O’odham assist the Lehi settlers in digging a new canal system, the use of which would benefit all. The following year, the larger Mesa Company would arrive and settle up the hill.

1878 Attempt to Steal Native Farms: Non-native settlers attempt to make legal claim to lands on the north side of the Salt River that have been cleared, fenced, and worked for years by the Onk Akimel O’odham. Agent Stout and Captain Adna Chaffee of Fort McDowell urge the U.S. government to legally recognize and preserve water and land rights for the O’odham and Piipaash settled along the Salt River.

January 10, 1879 Original Salt River Reserve: President Rutherford B. Hayes, by executive order, establishes additional reserve lands for the O’odham-Piipaash to protect the Salt River villages and farmland. It encompasses approximately 680,000 acres (estimate), including the Salt River along its entire length eastward to the Apache Reserve. This order causes a public outcry among the roughly 5,000 non-native settlers and speculators claiming land within the boundaries of this reserve.

June 14, 1879 Revised Salt River Reserve: President Hayes, by executive order, dissolves the previous January 10th executive order and establishes a much smaller Salt River Reserve, consisting of just 46,627 acres (current SRPMIC consists of approx. 54,585 acres). The Akimel O’odham and Piipaash, now live on two separate reserves that eventually become the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) and the Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC). The Phoenix metropolitan area develops and expands upon land that was O’odham and Piipaash traditional territory and was once protected as the Salt River Reserve.

Important Terms

O’odham – People (the Pima refer to themselves and their linguistic relatives as such in their own language)

Akimel O’odham – River People

Onk Akimel O’odham – Salt River People

Tohono O’odham – Desert People

Piipaash – People (the Maricopa refer to themselves as such their own language)

Xalychidom Piipaash – Upriver People (A specific group of Maricopa who now primarily reside in the Lehi District of the SRPMIC)

Huhugam – An Pima word used in reference to their deceased ancestors

Hohokam – An archaeological term (borrowed from the Pima language) used to define a specific archaeological culture within an approximate time frame spanning from A.D.1-1450

Piipaa Nykor – A Maricopa term used in reference to their ancestors (lit. People from before/long ago)

Patayan – An archaeological term (borrowed from one of the Yuman languages) used to define a specific archaeological culture within an approximate frame spanning from A.D.500-1550